the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Fuelwood territorialities: Chantier d'Aménagement Forestier and the reproduction of “political forests” in Burkina Faso

Muriel Côte

Denis Gautier

This paper investigates the endurance of a national forest management programme in Burkina Faso called Chantier d'Aménagement Forestier (CAF), which focuses on the participatory sustainable production of fuelwood and is widely supported by international donors despite evidence of its shortcomings. We analyse the surprising persistence of the CAF model as a case of the territorialisation of state power through the reproduction of “political forests” – drawing on the work of Peluso and Vandergeest (2001, 2011). Analysing some the shortcomings and incoherencies of the model, we bring to light the role of non-state actors in the reproduction of the CAF as a “political forest”. We show that informal regulatory arrangements have emerged between state and non-state actors, namely merchants and customary authorities, over the production of fuelwood. We call these arrangements “fuelwood territorialities” because they have contributed to keeping the CAF's resource model unquestioned. With fuelwood territorialities, we draw attention to the role of non-state actors in the reproduction of “political forests”, that is, the process of state territorialisation through forest governance. This analysis helps clarify how certain areas, such as the CAFs, keep being officially represented as “forest” even though they are dominated by a patchwork of fields, fallows, and savannahs and do not have the ecological characteristics of one.

The word “forest” is polysemic; it has a diversity of meanings that reflect not only a diversity of ecological definitions but also power relations over territory. In Burkina Faso, for example, many forest resource users whose first language is Mooré use the word weoogo, which best translates into English as “bush”. This word designates an area away from dwellings that may or may not be populated with trees, but it is commonly used as a translation for the word “forest” in French, the official state language in Burkina Faso. Interestingly, the first author once noticed that an area changed name when it became part of a state policy to formalise the area as a state forest: neighbouring residents stopped using the word weoogo to refer to the area under new official management and started using the term forêtwa, a vernacular pronunciation of the French word forêt. This was odd because the new word forêtwa did not designate a new landscape category – the drylands bush area previously referred to as weoogo was essentially unchanged. Rather, the change of term reflected a jurisdictional change, as the place previously referred to as weoogo was no longer under unofficial customary control, but under official state control. This anecdote illustrates that what we refer to as “forest” is not only a matter of ecology but also the product of socio-political processes and relations of territorial control. The diversity of forest definitions is not a problem in and of itself, but it can become problematic for the management of forest resources: if the definitions of what a forest is, where it starts and ends, cannot be agreed upon, how may it be possible to determine where forest management programs ought to take place? See Côte et al. (2018), the introduction to this special issue. In this paper we are particularly interested in the conditions under which some places are officially designated as “forest” and continue to be chosen by policymakers and donors for forest management even if they do not have the features of “forests”.

We tackle this issue through the case of the Chantier d'Aménagement Forestier (CAF, which translates into English as “forest management worksites”), a participatory forestry model for the sustainable production of fuelwood in Burkina Faso. This model has emerged in 1986 with the aim to “rationalise” fuelwood production through the implementation of participatory forestry within specific areas. Many of these areas were previously gazetted under the French colonial regime (forêts classées), and neighbouring residents were forbidden to clear natural resources for agriculture there. Under the CAF model, parts of gazetted areas, also called CAF areas, were opened up to neighbouring residents for the production of fuelwood. The model relies on the creation of woodcutter cooperatives made up of neighbouring residents and called forest management groups (FMGs, groupements de gestion forestière in French) that are in charge of sustainable fuelwood production and commercialisation. The FMGs that operate in CAF areas are meant to meet the fuelwood demand of main cities, especially the capital city, but the model has many shortcomings. Namely, the majority of fuelwood that is consumed in Burkina Faso is actually produced outside CAF areas, and within CAF areas forest regeneration has been hard to maintain. Despite these shortcomings, the model has expanded considerably – there are nowadays at least 26 CAFs (MEDD, 2013a), and the model has also attracted significant international donor funding, the most recent being from the Forest Investment Program (FIP), a global forest management scheme that aims to prepare countries for the international Reduction of carbon Emissions from Deforestation and land Degradation (REDD+) initiative. In this paper we investigate the conditions under which the expansion of the CAF model has taken place despite its shortcomings.

Our analytical point of departure is that CAF areas share characteristics with “political forests”, a concept proposed by Peluso and Vandergeest (2001, 2011) that characterises “lands that states declare as forests” and that “are a critical part of colonial-era state-making both in terms of the territorialisation and legal framing of forests and the institutionalisation of forest management as a technology of state power” (Peluso and Vandergeest, 2001:762). This notion is useful because it proposes that sites declared as forests are not only demarcated as such for their ecological characteristics but also instrumental to the territorialisation of state power. It suggests that political economic interests, as well as ecological scientific criteria, underlie the demarcation and maintenance of certain sites as “forests”. In this paper we extend this notion to the case of the CAF model in Burkina Faso, and we analyse the political economic relations around the production of fuelwood through which CAF, as a “political forest”, is reproduced.

We call these political economic relations “fuelwood territorialities”. They characterise the convergence of state and non-state actors' interests in the production of fuelwood resources as the CAF territorial model lands on the ground. We show that within CAF areas, the model has better served the interests of wholesale fuelwood merchants rather than those of FMG cooperatives, but this has not been brought into question by the government, partly because it would jeopardise its chance to secure international funds for forest management in Burkina Faso. Outside CAF areas fuelwood production is largely considered as informal but it is actually regulated by a system of fuelwood permits delivered by the central forest administration. This official regulatory arrangement has been difficult to apply in practice, however, because state presence is too sparse to apply it on the ground, and informal regulative arrangements have emerged between local forest agents and customary authorities. We call these relations between state and non-state actors “fuelwood territorialities”, and we argue that they contribute to the state territorialising effect of keeping CAFs as official “forests” despite the model's shortcomings.

With this analysis we hope to advance an understanding of the conditions under which “political forests” are reproduced. Rather than being coercively imposed from above, we show that state forest policy is reproduced through the convergence of specific state and non-state political economic interests in the production of forest resources, in this case fuelwood resources. The distinction between fuelwood merchant and customary territorialities is important because it shows that different kinds of non-state actors can become enrolled in the process of state territorialisation through forest policy, and it shows that different kinds of state–non-state relations occur within and outside “political forests” (see also Gautier and Hautdidier, 2012; Hautdidier et al., 2004). The fuelwood territorialities we describe here are not meant to be exhaustive – for example other non-state actors may also be involved in the reproduction of “political forests” through the convergence of interests with state actors. They are rather illustrative of the role and different kinds of state and non-state political economic relations around forest resource production, which sustain forest policy despite its shortcomings.

Our analysis is based on the first author's research on the mismatches between fuelwood policy and practice in Burkina Faso, including ethnographic field research in the Yatenga province between 2011 and 2012 and regular visits since, and on the second author's long-term research engagement on fuelwood policies in the Sahel, particularly in Burkina Faso. This combined research experience provides a basis to put together a realistic picture of the CAF policy on paper and on the ground. We start with a characterisation of “fuelwood territorialities” and the way they help us understand the reproduction of “political forests”. We then present a brief history of the CAF model, its popularity, and its resonance with the “political forest” and its shortcomings. This is followed by our description of two kinds of fuelwood territorialities, involving relations between state agencies with merchant and customary authorities, respectively inside and outside CAFs, and the way these relations make the CAF model difficult to abandon as a site of forest management in Burkina Faso.

Forest management policymakers often assume that there is such a thing as “forest” out there, waiting to be managed. However, work in political ecology has demonstrated that nature is always “situated” (Haraway, 1991), in the sense that “nature” is always seen from somewhere, and different actors have different ways of defining “forest” (Goldman et al., 2011). However, this poses a dilemma for the sustainable management of forest resources, for if forest can be defined in multiple ways, how can appropriate forest management sites be found? The work of Nightingale (2003) illustrates this dilemma in Nepal, where she analysed the discrepancies between local forest users' and aerial photographic representations of how a forest area improved and degraded. Rather than reifying one account over another and trying to get at the “truth”, she analysed why definitions differed and showed that discrepancy could be explained as a reflection of the competing relations of control over the area between local users and central government. Her work shows that meanings of “deforestation” and “forest” are entangled with competing claims for land control, and they need to be continually examined critically if their associated policies are to have any effect on forest dynamics.

Peluso and Vandergeest's (2001, 2011) concept of the “political forest” is useful here because it takes the political dimensions of defining forest into consideration. In our view, this work articulates two key political dimensions of forests. Firstly, it emphasises that “forests” are “not natural or universal categories of knowing but constructions” (Peluso and Vandergeest, 2001:801), and these constructions play a part in processes of state territorialisation. They make this argument through several cases in South-East Asia, where they showed that areas officially referred to as “forests”, such as gazetted and reserved forests, came together not only through scientific logics of conservation but also through political logics of control over space and populations. Key to this state territorialisation process is the way government policies have drawn on scientific forestry that advocates the creation of spaces dedicated to forestry and separated from agriculture, thereby criminalising the customary land use practices of nearby residents. This dimension echoes the case of the CAF model we will describe below in Burkina, which relies on the separation of forestry and agriculture but also draws on participatory governance principles to legitimise this separation.

Secondly, “forest” is political because government logic underlying forest policy is often challenged in practice, and notions of “forest” and forest management are “contested both within the states' apparatus and by its intended subjects” (Peluso and Vandergeest, 2001:800). Peluso and Vandergeest illustrate such contestation from within the state as an example, with two quotes from colonial officers with conflicting opinions about what to do with the residents surrounding valuable forest areas (Peluso and Vandergeest, 2001:761-2). In other contexts, forest policy can also be more openly challenged, or transformed on the ground when the presence of government is scarce, and policy application is scanty. In Ghana, for example, Wardell and Lund (2006) demonstrate that forest governance is well qualified as a product of “the rents of non-enforcement” rather than as a product of government law enforcement, because forest reserves have created an “illegality” that is a source of monetary and political rent-seeking for both local customary chiefs and forest agents. In Senegal, Blundo (2011) analyses other kinds of informal arrangements between state forest agents and international NGOs as cases of the “informal privatisation” of ground-level forestry service. So when the application of forest policy falls short, a number of non-state actors, such as customary authorities and international NGOs in these cases, become involved. Rather than undermining state territorialisation, their involvement can be constitutive of maintaining forest policies and “political forests” when their interests converge with those of states.

In this vein, Bassett and Gautier (2014) argue that territorialisation is “polycentric” to emphasise a “contrast to the state-centric focus of the territorialisation literature” and “to illustrate that the production of territories springs from multiple sources and locations” (Bassett and Gautier, 2014:3). We draw on this “polycentric” understanding to state territorialisation and to conceptualise the reproduction of “political forests” not only as a result of coercive state forest policy imposed from above but also through the relations between state and non-sate actors around the production of forest resources. A good example can be found in the work of Gautier et al. (2011) in Mali, where government policy aiming to institutionalise village-level fuelwood “harvesting spaces” under the control of professional woodcutters associations actually opened up opportunities for customary authorities to assert territorial claims and political leverage with central government. In this case, the contestation did not bring down fuelwood policy; on the contrary, the tacit government recognition of customary control over these “harvesting spaces” was part and parcel of the reproduction of fuelwood policy. Drawing on these insights, we conceptualise fuelwood territorialities as converging political economic interests between state and non-state actors around the production of fuelwood resources, which contribute to the state territorialising effect of keeping certain areas demarcated officially as “forests” despite forest policy shortcomings.

Below we illustrate “fuelwood territorialities” in the case of the CAF model in Burkina Faso, and we show the role they play in the reproduction of CAF areas as “political forests”. We start with a brief history and description of the CAF model and its popularity with international donors, which partly explain why it has been reproduced. However, this paradigm is not applied to the letter, as we show in Sects. 4 and 5. Rather, the CAF model is appropriated on the ground in ways that profit particular interest groups around the production of fuelwood, the merchants inside CAFs, and local customary authorities outside CAFs. These different “fuelwood territorialities” are important because they help us account for the ways in which the CAF model, as a “political forest”, is reproduced over time.

The CAF is a national forestry model that emerged in the mid-1980s in Burkina Faso, with the aim to “rationalise” fuelwood production. It emerged at the intersection of a rising concern about fuelwood shortages in the Sahel in the 1970s (Ribot, 1999, 2001) and the growing popularity of participatory approaches to forest resources management worldwide in the 1980s (Bertrand et al., 2006). The model shares features with the “political forest” described by Peluso and Vandergeest (2001, 2011): it is implemented within places gazetted under the French colonial regime, and it is based on scientific forestry principles that spatially segregate agriculture from forest production, thereby also criminalising agricultural practices that may take place within CAF areas. The model has been very popular with donors interested in supporting forest management. Key to this popularity has been the participatory approach underlying the CAF model, but biomass within CAF areas has been hard to maintain. In this section we describe the rise of the CAF model as a “political forest”, its shortcomings, and its puzzling popularity with donors.

Before the CAF model emerged, concerns for protecting the natural resource base in Burkina Faso translated into large state-monitored planting programmes in the 1970s. Large-scale plantations under state control proved to be rather inefficient, and their failure led to the adoption in the 1980s of a small-scale village-level tree planting project called bois de villages (village woodlands), but these were not dedicated to be a source of fuelwood. Village-based plantations were of limited size, generally planted with eucalyptus, and sold as construction wood. As elsewhere in the subregion, the national effort of tree plantation has been abandoned since the 1980s to the profit of participatory natural forest management, with a double objective of conservation and fuelwood production (Gazull and Gautier, 2014). The CAF model originated in this context, under the brief but intense 3-year revolutionary regime led by the highly charismatic late Captain Thomas Sankara, and within what he called “the three struggles” against deforestation (including the fight against abusive woodcutting, bush fires, and the wandering of livestock). The first CAF worksite was launched in 1986 and funded by the FAO under a project called “Management and exploitation of forests to supply the city of Ouagadougou with firewood” (Projet PNUD/FAO/BKF/85/011). Despite the political rupture after the fall of the Sankara regime in 1987, the project was maintained and indeed grew. In 2013 there were 26 earmarked CAF areas, and there are currently over 400 FMGs (the woodcutter cooperatives that manage CAF areas) registered throughout the country (MEDD, 2013a).

The CAF model reflects a dominant forestry ontology that sees the overexploitation of fuelwood as a crux of deforestation dynamics in the Sahel. It aims to produce fuelwood to supply the urban centres (mainly Ouagadougou), whose demands are perceived as the largest and are thereby also the main driver of fuelwood-induced deforestation. The model is inherited from former colonial forestry in two main ways. Firstly, CAF areas are mainly located in the Centre-West region and in areas that were initially reserved by French colonial administrators as “gazetted forests”. These were all reserved between the 1930s and 1950s through a control regime that excluded residents' agroforestry practices; their reservation aimed to provide the colonial administration with timber wood, namely for the construction of a railroad between Abidjan and Niamey, and they are still gazetted to this day (Côte, 2015). As the Ministry of Environment explained, “the idea behind it was for the state to open up the gazetted forests and transform them into forests with a regime of controlled exploitation because, at that time, studies started showing that it was possible to exploit a forest while conserving it though a system of rotation” (Ministry en Environment staff, Ouagadougou, 11 April 2012). So the CAF model is applied in these gazetted areas because of the government's progressive commitment to emerging participatory forestry approaches in 1980s, but also because forest resources within these areas are relatively abundant, as they are situated along important rivers, and they are therefore considered fit for fuelwood production.

Secondly, the CAF model is based on contemporary participatory forestry paradigm, but it also continues to draw on colonial forestry norms. These norms include the designation of areas subdivided in forest management worksites under specific fuelwood management plans and terms of reference (Gautier et al., 2015). In order to create a CAF, a forest management plan (plan d'aménagement forestier) must be elaborated, and it must identify when and where fuelwood can be cut – typically a CAF area is divided into 15 plots that are exploited each year on rotation basis of 1 plot per year over 15 years.1 The participatory aspect of the CAF model comes from the fact that the plots are managed by local woodcutter cooperatives, the FMGs who provide the woodcutting workforce and benefit from fuelwood sales. The members of the FMGs work accordingly with scientific ecological calculations that are perceived as necessary to ensure the renewability of forest resources. The management plan is overseen by forestry technicians who are hired to offer woodcutters training (in cutting technics, the regeneration of exploited plots by direct seedling, and early bush fire practice) and it must be validated at ministerial level. In other words the CAF model is an agreement, or a fuelwood concession, between the central state and the FMGs, but the latter have limited access and management rights.

The CAF model is presented as state-of-the-art forestry in the wider Sahel region, and its participatory aspect has been instrumental in securing external funding for national forest management programs in Burkina Faso. For example in 2010, Burkina was chosen with 5 other countries out of the 48 ones proposed worldwide for the global FIP's pilot project for a global REDD+ program (MEDD, 2013b:41). There are two main components to this program that amount to USD 30 million in total, half of which is dedicated to the “Gazetted Forests Participatory Management Project for REDD+” (PGFC/REDD+) funded by the African Development Bank. This significant funding is based on the fact that “the need for increased community participation in forest management has been gradually recognised during the past three decades” and that it has “implemented a participatory management of gazetted forests through FMGs geared towards the sustainable exploitation of forest resources, mainly wood.” (AfDB, 2013:4).

The popularity of the CAF model is surprising, however, because it has not had the expected ecological effects. Firstly, a large majority – an estimated 85 % – of the fuelwood consumed in cities is actually produced outside CAF areas. In theory, fuelwood commercialisation outside CAFs is not illegal if it is done with a fuelwood permit, but it is potentially fraudulent. CAF areas are considered as biologically fit for fuelwood production in Burkina Faso, as “managed forests”, marked out and managed by a group of professional woodcutters (Gautier and Compaoré, 2006). In contrast the rest of the country is not organised according to a “management plan”; for this reason, the fact that the vast majority of fuelwood that is commercialised actually comes from outside CAF areas is generally considered as a failure of the model (Sawadogo, 2007; Ouédraogo, 2009). Secondly, within CAF areas, natural regeneration has been hard to maintain. Sawadogo (2007) shows that the direct seedling used for promoting the regeneration and the rebuilding of ecosystems within the CAFs fails to compensate the wood destocking from trees that takes several decades – more than the 15 years devised in a typical management plan – to reach their maturity (see Tanyi, 2017, and Puentes-Rodriguez et al., 2017, for similar results). Finally, neighbouring residents notoriously extend agricultural fields within the CAF areas (Guirro Ouedraogo, 2003; Hagberg, 2000; Zougouri, 2008).

So like the “political forest”, CAF areas are lands set aside for a particular forest management purpose and, according to the CAF model, these areas are officially marked out as the only areas biologically fit for fuelwood production in Burkina Faso. However, evidence shows that only a very small part of the wood coming out of CAF areas actually supplies the city of Ouagadougou, that biomass decreases within CAF areas at the end of their rotation, and that CAF areas are not composed so much of a forest landscape but of a mosaic of field and woodlands. Despite these shortcomings, the CAF endures as model for official “forests” in Burkina Faso. Key to the reproduction of the CAF model has been the support of international donor funding, and key to this support has been the combination of scientific forestry around the sustainable production of wood and the involvement of “community participation” through FMGs created for the CAF model. Below we analyse the political economic relations underlying fuelwood production within CAF areas, and we show that while the model aims to benefit the FMGs, wholesale fuelwood merchants actually benefit the most out of fuelwood production within this model. We show that the government is aware that FMGs are losing out but, rather than questioning the model and the merchants' upper hand, it calls for a multiplication of CAF areas, an expansion of the model, to address the issue. We call CAF areas “merchant fuelwood territoriality” not because merchants are trying to establish territorial control over CAF areas but because the convergence of merchant and state political economic interests contributes to the reproduction of the CAF model as a “political forest” and to its state territorialising effect. In the next section we examine the CAF model in greater detail, with an emphasis on these various relations of fuelwood production.

The CAF model aims to “hand over” the management of CAFs areas to neighbouring residents and many of the model's features reflect this participatory underpinning. FMGs must be constituted of local residents, operate as a local woodcutter cooperative, and ideally have a monopoly over fuelwood production within their CAF areas. A CAF comes together after each village neighbouring the CAF area sets up their FMG group, which together form a union of FMGs. The FMG agrees on a management plan that is drawn and maintained with the technical assistance of a team of forest technicians headed by a technical director. Part of the fuelwood sales generated by FMG woodcutters contributes to a forest management fund (fond d'aménagement forestier in French) that pays the technicians' salaries. The fund also finances technical activities in the CAF including woodcutters training to cutting technics, the regeneration of exploited plots by direct seedling, and early bush fire practice. Another smaller part of fuelwood sales contributes to a village development fund (fond d'aménagement villageois in French) that aims to finance non-forestry activities in the villages such as pasture management, or other activities like hunting or the gathering of non-timber forest products outside the CAF worksites.

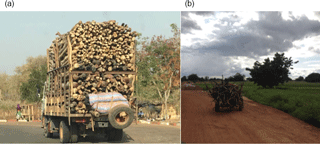

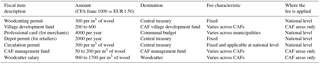

In practice this participatory model has proven difficult to realise (Delnooz, 2003). Firstly, fuelwood production within CAFs is subjected to more burdensome regulation than outside CAFs, which has played against FMGs and in favour of wholesale fuelwood merchants. Table 1 details the fiscal regime pertaining fuelwood production in Burkina Faso. It shows that outside CAFs woodcutters must only pay woodcutting and circulation permits, but FMG woodcutters within CAFs must also contribute to the forest management and village development funds.2 In 2002, the cost of producing 1 m3 of wood (CFA 2200 in this case) broke down into 14 % attributed to state taxes, 50 % to woodcutters, and 36 % to the two funds that are only apply to CAF (Kambire et al., 2015:28). Fuelwood sold by FMG woodcutters is therefore inevitably more expensive than fuelwood produced outside CAFs. According to Ouédraogo (2006) the main issue with the CAF model is that the prices for the cubic metre of wood is fixed by the government, and this price is too low and has not changed for the last 20 years. The production of fuelwood within CAF areas has provided merchants the opportunity to pick up larger quantities of wood in one single site, compared to production outside CAFs that is smaller-scale and more dispersed, and merchants have generally benefitted from this model despite the fact that fuelwood is cheaper and less regulated outside CAFs.

Figure 1Truck picking up fuelwood within a CAF (a) and a wagon carrying fuelwood that was gathered outside CAF areas (b) (source: authors).

Table 1Fiscal regime over fuelwood production in Burkina Faso (source: adapted from CILSS, 2007:20).

Secondly, profits from the sale of fuelwood produced within CAFs have also largely benefitted fuelwood merchants rather than FMGs. The market chain analysis undertaken by Ouédraogo (2007) in 2005, for example, examined the structuration of profit from fuelwood sales based on data collected from 8 CAF sites and 98 commercial intermediaries (merchants and retailers). The study shows that based on the fuelwood consumer price, 28 % of profits are generated by merchants, 12 % by retailers in the city of Ouagadougou, and only 9 % constitute the woodcutter's revenue. Coulibaly et al. (2007) and Bouda et al. (2011) come to similar findings, furthermore emphasising that 50 % of the share goes to central treasury (including not only fuelwood production taxes but also those collected from merchants and retailers).

These shortcomings are known among official circles, but instead of bringing into question the political economic structure of the model throughout the entire value chain, from the tree to the consumer, the central government advocates a further expansion of the model, including the same actors, powers, and practices as they are at present. Responding to UK and USA donor concerns about the CAF model in 2015, the government acknowledged that “wood producers cannot make consistent revenues at the moment” and that “the fuelwood exploitation …cannot be sustainable because it does not ensure the replacement of the wood that was cut down”. The same document further explains that “[i]t is the marginal nature of the total production of forest management units [CAF] that inhibits its contribution to improving the governance of forest resources management”.3 In other words, it is suggested that if there were more CAFs these shortcomings would go away, and the upper hand of merchants over the regulatory chain is left unquestioned.

So CAFs are fuelwood concessions allocated to woodcutter cooperatives, the FMGs, aiming to rationalise fuelwood production by geographically concentrating fuelwood production in the most biologically fit forests. In practice this has been difficult to realise, partly because FMG cooperatives have struggled to make sufficient profits. Instead the CAF model has largely benefitted fuelwood merchants who are able to pick up large quantities of fuelwood at a price that allows them to come out as the winners of profits along fuelwood chain. The central government has not challenged this significant deviation from the CAF participatory vision and in fact emphasised the low profits of FMGs as an argument to secure external funding that will expand the CAF model further. The convergence of merchant and government political economic interests around keeping the CAF status quo contributes to reproducing the CAF model as a “political forest” in Burkina Faso. We call it merchant fuelwood territoriality because it contributes to further expansion of territorial state power in Burkina Faso through this fuelwood policy and through the expansion of the CAF model. Below we show that outside CAF areas, a different kind of relation and converging interests between state and non-state actors, which we call customary fuelwood territoriality, also contributes to indirectly reproducing the CAF model in Burkina Faso.

In this section we bring to light another kind of fuelwood territoriality that occurs outside CAF areas and helps us understand the endurance of the CAF model in Burkina Faso. Above we mentioned that fuelwood producers outside CAFs are subjected to less oversight than the FMGs operating within CAFs: woodcutters operating outside CAFs must only obtain a permit with a localised forest agent. This regulation has also been hard to apply in practice however, and the scanty regulation over fuelwood has generated discontent among resource users. Informal institutions, which we call tiis nanamse (sing. tiis naaba) to follow the vernacular terminology, have emerged within this discontent and from tacit agreements between the local forest agent and landholding families with informal customary authority over land and natural resources.4 We focus on field research conducted on everyday forms of fuelwood regulation, in the district of Séguénéga, North Burkina Faso (see map below). We describe below the emergence of the tiis nanamse institution out of the informal arrangements between state forester and non-state customary authorities. We show that this informal institution contributes to appeasing local discontent, and to keeping the wider deficient fuelwood policy, including the CAF model, unquestioned. We call it customary fuelwood territoriality because it has maintained the status quo over fuelwood policy in Burkina Faso and thereby also contributed to expanding territorial state power.

The fuelwood permit delivered by the state forester in the district of Séguénéga has generally not been popular with residents. It comprises a woodcutting and a wood transportation tax, which together amounts to CFA 750 for a cartload.5 However, forest agents have notoriously weak enforcement capacities.6 Fuelwood is often collected and sold in places far from the forest agent's office, and woodcutters complain that it is impractical to travel to the forest agent's office to pick up the required authorisation (source: woodcutter, district of Séguénéga, interview on 21 February 2012). Poor law enforcement has also become a problem for local residents who see their resources declining and who complain about deforestation:

Before, people did not sell firewood so much, but now everyday you see carts loaded with wood coming out of our bush. It is people from the neighbouring village. They have depleted their bush, and now they come to get ours. (Resident, district of Séguénéga, group interview on 4 April 2012)

Selling firewood has indeed become a profitable activity. Residents complain that the shortage of rain causes deforestation, but also that “the fuelwood permit really does not help either” (resident, district of Séguénéga, interview on 15 April 2012).

For a number of customary leaders, deforestation dynamics are partly due to the fact that forest law has undermined customary rules, such as forbidden places (zii kidse), traditionally exercised by autochthonous family lineages:

Now we don't have rules anymore; we used to have customs but the law of the whites came and now we have no control over the bush. (Group interview, district of Séguénéga, on 9 May 2012)

Another leader more specifically complained that

The person who has the paper [fuelwood permit] can do what he wants, and if we see somebody in the bush doing things against our rule, we cannot forbid them because he shows the paper. If there wasn't this paper, would it be possible for anybody to come and cut greenwood here? If they cut greenwood they couldn't get out of the bush, we wouldn't let them, but since they have the paper we can't stop them! (Village chief, district of Séguénéga, interview on 13 April 2012)

So in the areas where there is no CAF, national fuelwood policy has erased customary norms and, in a context of increasing fuelwood demand, resource users feel that weak state capacity exacerbates deforestation because they are not able to exclude woodcutters and fuelwood merchants from outside their village.

In several villages around the town of Séguénéga, individuals referred by some residents as tiis nanamse intervened to patch up policy deficiencies. These individuals are often members of first-comer lineages because the latter generally have political authority over nature and over what may and may not be done in the bush, outside inhabited areas. Their authority encompasses rituals related to land fertility, and they often arbitrate disputes taking place in the bush and about land, such as the theft of cattle and tree fruits, and the boundaries between fields (Kuba et al., 2003). In a village close to Séguénéga, the district capital, the tiis naaba created a new informal rule, a “fuelwood park” close to the small informal village marketplace, as a way to regain control over places where fuelwood would be collected. According to this new informal system, the fuelwood brought to the park could only be gathered by woodcutters from the village, and fuelwood merchants taking it to Séguénéga had to pick it up there for an informal fee of CFA 300 (the equivalent of the woodcutting tax), which was meant for the woodcutters from the village. The tiis naaba effectively imposed a monopoly over fuelwood production for woodcutters from his village, thereby aiming to address discontent about the lack of control over where and by whom fuelwood is collected (village development representative member, district of Séguénéga, interview on 2 April 2012; tiis naaba, village in the district of Séguénéga, interview on 30 January 2012). He meant to replace the official woodcutting tax with his own informal receipt, while leaving it to the forest agent to collect the transportation tax.

The measure proved difficult to maintain, but with the tacit agreement of the local forest agent, the tiis naaba was able to keep prohibiting the activities of woodcutters from outside the village. Woodcutters and merchants (often a single operator) from outside the village did not initially oppose this as it saved them the trouble of collecting fuelwood, and it did not incur additional spending for them. It became a problem, however, when some woodcutters were stopped by the forest agent transporting fuelwood without an official permit. They explained the “new” system to the forest agent and showed the informal receipt they were given by the tiis naaba. Although this fee was informal, the forester did not oppose it as long as the woodcutters agreed to it in addition to the CFA 750 official fuelwood permit, as it contributed to a better oversight of forest resources. The forester justified this decision by referring to tiis naanamse as “resource persons”:

They may not be the village chief, they may not be the CVD [local administrative village representative], but you have to go through them to get things done. (Forester, Séguénéga, interview on 4 May 2012)

The woodcutters of course complained about this sudden increase of expenses and they stopped collecting wood within the customary territory of Sima (woodcutter, district of Séguénéga, interview on 21 February 2012). As a result the tiis nanamse were no longer able to collect a fee, but they were able to successfully exclude woodcutters and merchants from outside their village from collecting fuelwood in “their” bush and thereby also keep contestations over a deficient fuelwood permit policy at bay.

In this last section we bring to light another kind of fuelwood territoriality, one that takes place outside CAF areas but that also contributes to keeping the status quo around the current fuelwood policy in Burkina Faso. We show that outside CAF areas official fuelwood regulation has undermined customary rules, and customary authorities have lost control over who comes in and out of what village residents consider “their” bush. Within this context, informal institutions have formed as a way to regain control over the bush. The tiis nanamse informal regulation described here aimed not to fight the official fuelwood permit but rather to exercise greater control over “their” bush, which they obtained eventually with the tacit agreement of the local forester. The informal arrangement described here between state and non-state actors is not a deviation but an integral part of the reproduction of the CAF model as “political forests” in Burkina Faso because, by patching up the incoherence and contradictions of a national fuelwood policy built around the CAF model, it maintains their official status quo over these policies. We call such arrangements customary fuelwood territoriality because they essentially contribute to reproducing national fuelwood policy and thereby also legitimise territorial state power in Burkina Faso.

This paper questioned the conditions under which certain sites are repeatedly chosen for forest management initiatives in a context where definitions for forests are multifarious and where the areas referred to as “forest” do not necessarily have forest ecological characteristics. We have brought this question up through the example of the endurance and expansion of the Chantier d'Aménagement Forestier in Burkina Faso, a participatory forestry model that aims to rationalise sustainable fuelwood production. The CAF model continues to be reproduced, namely with the support of international donors like the Forest Investment Program, and despite the fact that CAF areas have not been able to maintain their biomass. We have argued that the model has produced political opportunities for non-state actors that converge with government interest in reproducing the CAF model. These converging political economic interests between state and non-state actors, although deviations from policy vision, have been integral parts of reproducing the CAF model and its state territorialising effects, and this is why we call them “fuelwood territorialities”.

We analysed the configurations of state and non-state political economic interests within and outside CAF areas. We showed that within CAF areas, the production of fuelwood has worked in favour of large-scale fuelwood merchants: CAF areas allow merchants to collect and trade larger amounts of wood than outside CAF areas, and they have reaped the largest part of fuelwood production profits compared to the FMGs that the CAF model aims to empower. Donors have challenged the failure of the CAF model to empower FMGs but, as we showed, the central government has not brought into question the upper hand of merchants and rather advocates for a multiplication of CAF areas for the model to work to its full participatory potential. The convergence of non-state merchant and government interests contributes the territorialisation of state power by leaving the CAF model largely unquestioned. Outside CAF areas we analysed the everyday fuelwood regulation in the district of Séguénéga, where we showed that the inapplicability of government regulation has given way to a new informal institution, the tiis naaba, that emerged from compromises between state and non-state customary authorities and that overall maintains the status quo over incoherent fuelwood policy and the CAF model more widely. This latter configuration is different from the convergence of interests between merchants and government described before, namely because it involves different kinds of state and non-state actors, and relations at different levels – the merchants' interests converging with national state actors, while the customary ones converge at local forest agents. Although these relations appear to be deviations from the fuelwood policy vision in Burkina Faso, we have shown that they are integral parts of its reproduction.

With this analysis we propose a way to approach the conditions under which the “political forests” described by Peluso and Vandergeest (2001, 2011) are reproduced over time. The CAF model strongly resonates with the “political forest”: it takes place in the same sites as areas gazetted as “forests” under French colonial rule; CAF areas are delineated based on the “imported” scientific forestry idea that fuelwood production needs to be contained in areas that are segregated from agriculture; and the CAF model is largely “meant to enable state agencies to regulate the socio-spatiality of floral and faunal forest production, reproduction, extraction, and protection” (Peluso, 2011:815) – in other words where and by whom forest resources are produced. Drawing on Bassett and Gautier's (2014) polycentric approach to territorialisation processes, we emphasized the role of non-state actors in state territorialisation.

Finally, returning to the issue of forest policy that takes place in contexts where “forest” has a diversity of meanings, we have emphasised in this paper that defining and demarcating “forests” is part of a political relation between different groups – as also illustrated in the anecdote introducing this paper. It is political in the sense that demarcating and officially keeping certain areas as “forests” may be less a product of careful scientific assessment than of the convergence of particular state and non-state political economic interests as those illustrated in this paper. We see interesting further research avenues in the role that other non-state actors play in the reproduction of “political forests” – such as the convergence of donor and government political economic interests as another fuelwood territoriality, and the role of the participatory forestry paradigm in cementing that relation, or the converging relations between resource producers and local governments whose role has expanded throughout the world with the adoption of forest decentralisation reforms. Fuelwood territorialities could also be relevant in other resource contexts – such as national parks or charcoal production areas – that also constitute political natures, and where non-state actors are also involved in the territorialisation of state power through national resource management policies. Such research would help further understand how certain areas, like the CAFs, continue to be reproduced as national natures in the midst of their incoherence and contradictions on the ground.

This article is founded on research funded by the ESRC and by the Mosse Centenary Fund at the University of Edinburgh. For reasons of data protection, the transcriptions of interviews that were part of the research methodology are not publicly available.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We are grateful to Ross Purves and Flurina Wartmann for their

thought-provoking comments on a draft version of this paper, as well as

participants at the workshop in Stels on “the trouble with defining forest:

semantics, ontology, territoriality” in June 2016 for their comments and

discussion on an earlier draft. We would also like to thank three anonymous

reviewers for their constructive comments. Any errors in this paper remain of

course our own.

Edited by: Benedikt

Korf

Reviewed by: three anonymous referees

AfDB: Gazetted Forests Participatiry Management Project for REDD+ (PGFC/REDD+), Country: Burkina Faso, Project Appraisal Report, July 2013, African Development Bank, 2013.

Bassett, T. J. and Gautier, D.: Regulation by territorialisation: political ecology of conservation and development territories, EchoGéo, 29, 1–7, 2014.

Bertrand, A., Gautier, D., Konandji, H., Mamane, M., Montagne, P., and Gazull, L.: Niger and Mali: Public policies, fiscal and economic forest governance policies and local forest management sustainability, Policy and distributional equity in natural resource commodity markets: commodity-chain analysis as a policy tool, France, CIRAD, 2006.

Blundo, G.: Une administration a deux vitesse: projets de développement et construction de l'Etat au Sahel, Cah. Etud. Afr., 202–203, 427–452, 2011.

Bouda, Z. H.-N., Savadogo, P., Tiveau, D., and Ouedraogo, B.: State, Forest and Community: Challenges of Democratically Decentralizing Forest Management in the Centre-West Region of Burkina Faso, Sustain. Dev., 19, 275–288, 2011.

CILSS: Les professionnels du bois au Burkina Faso. Rapport final, Cellule nationale de coordination du PREDAS, Programme PREDAS CILSS-PREDAS (Projet 8 ACP-ROC-051), Ouagadougou, CILSS, 2007.

Côte, M.: Autochthony, democratisation, forest: The politics of choice in Burkina Faso, in: Responsive Forest Governance Intitiative, edited by: Murombedzi, J., Ribot, J., and Walters, G., Dakar: CODESRIA, 2015.

Côte, M., Wartmann, F., and Purves, R.: The trouble with forest: definitions, boundaries and values, Geogr. Helv., in review, 2018.

Coulibaly, S., Compaoré Kafando, F., Agnamou, A., Kaboré, S., Nébié, Z., Rouamba, T., and Soulaïma, I. H.: Analyse des impacts Financiers et économiques de la filière bois-énergie organisée approvisionnant la ville de Ouagadougou, EASYPol, Ressources pour l'élaboration des politiques, 2007.

Delnooz, P.: Aménagement forestier et gestion communautaire des ressources naturelles: participation ou négociation?, presented at: Communication au séminaire international de l'université de Ouagadougou, Les organisations d'économie sociale dans la lutte pour la réduction de la pauvreté, January 2003.

Dié, L. M.: Rapport de base sur la Gouvernance Forestière au Burkina Faso, Information de base pour l'Atelier sur la Gouvernance Forestière au Burkina Faso, PROFOR/World Bank, Ouagadougou, 2011.

Gautier, D. and Compaoré, A.: Les populations locales face aux normes d'aménagement forestier en Afrique de l'Ouest, Mise en débat à partir du cas du Burkina Faso et du Mali, CIFOR, CIRAD/APEX/WRI, 2006.

Gautier, D., Garcia,C., Negi, D., and Wardell, D. A.: The limits and failures of existing forest governance standards in semi-arid contexts, Int. For. Rev., 17, 114–126, 2015.

Gautier, D. and Hautdidier, B.: Political ecology et émergence de territorialités inattendues: l'exemple de la mise en place de forêts aménagées dans le cadre du transfert d'autorité de gestion au Mali, in: Environnement, Discours et Pouvoir, L'approche Political Ecology, edited by: Gautier, D. and Benjaminsen, T., Quae, Versailles, 241–257, 2012.

Gautier, D., Hautdidier, B., and Gazull, L.: Woodcutting and territorial claims in Mali, Geoforum, 42, 28–39, 2011.

Gazull, L. and Gautier, D.: Woodfuel in a global changes context, Wires Energy Environ., 4, 156–170, 2014.

Goldman, M. J., Nadasdy, P., and Turner, M. D.: Knowing Nature, Conversations at the Intersection of Political Ecology and Science Studies, Chicago, University, Chicago Press, 2011.

Guiro Ouédraogo, A.: Problématique d'agression des forêts classées de Dinderesso et du Kou cas des exploitantes frauduleuses de bois des secteurs 10, 11, 21 et 22 de la ville de Bobo Dioulasso, Recherche de perspectives, Controleuse des Eaux et Forêts, Ecole Nationale des Eaux et Forêts, Bobo Dioulasso, 2003.

Hagberg, S.: Droits à la Terre et Pratiques d'Aménagement dans la Forêt de Tiogo, Environnement et Societe, 24, 63–71, 2000.

Haraway, D.: Siminans, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, Routledge, London, 1991.

Hautdidier, B., Boutinot, L., and Gautier, D.: La mise en place des marchés ruraux de bois au Mali: un événement social et territorial, l'Espace Géographique, 4, 289–305, 2004.

Kambire, H. W., Djenontin, I. N. S., Kabore, A., Djoudi, H., Balinga, M. P. B., Zida, M., and Assembe-Mvondo, A.: La REDD+ et l'adaptation aux changements climatiques au Burkina Faso, in: Document occasionel 123, Bogor Barat, CIFOR, 2015.

Karambiri, M.: Démocratie locale “en berne” ou péripéties d'un choix institutionnel “réussi” dans la gestion forestière décentralisée au Burkina Faso, in: RFGI working paper: CORDESRIA/UIUC/IUCN, 2015.

Kuba, R., Lentz, C., and Somda, C. N.: Histoire du Peuplement et Relations Interethniques au Burkina Faso, Paris, Karthala, 2003.

MEDD: Programme d'Investissement Forestier (PIF – Burkina Faso), Plan d'investissement forestier, 2011.

MEDD: Plan de préparation à la REDD (R-PP – Burkina Faso), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Ministère de l'Environnement et du Développement Durable, 2013a.

MEDD: Programme d'investissement Forestier. Projet de gestion décentralisée des forêts et espaces boisés, Cadre de gestion environnementale et sociale, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Ministère de l'Environnement et du Développement Durable, 2013b.

Nightingale, A.: A Feminist in the Forest: Situated Knowledges and Mixing Methods in Natural Resource Management, ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 2, 77–90, 2003.

Ouédraogo, B.: La demande du bois-energie a Ouagadougou: esquisse d'evaluation de l'impact physique et des echecs des politiques de prix, Varia, 2006.

Ouédraogo, B.: Filière bois d'énergie burkinabé: structuration des prix et analyse de la répartition des bénéfices',Bois For. Trop., 294, 75–88, 2007.

Ouédraogo, B.: Aménagement forestier et lutte contre la pauvreté au Burkina Faso, Developpement Durable et Territoires, available at: https://journals.openedition.org/developpementdurable/8215, Varia, 2009.

Peluso, N.: Emergent forest and private land regime in Java, J. Peasant. Stud., 38, 811–36, 2011.

Peluso, N. and Vandergeest, P.: Genealogies of the political forest and customary rights in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, J. Asian Stud., 60, 761–812, 2001.

Peluso, N. and Vandergeest, S.: Political ecologies of war and forests: Counterinsurgencies and the making of national natures, Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr., 101, 587–608, 2011.

Puentes-Rodriguez, Y., Torssonenm, P., Ramcilovik-Suominen, S., and Pitkänen, S.: Fuelwood value chain analysis in Cassou and Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: From production to consumption, Energy Sustain. Dev., 41, 14–23, 2017.

Ribot, J. C.: A history of fear: imagining deforestation in the West African dryland forests, Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 8, 291–300, 1999.

Ribot, J. C.: Science, user rights and exclusion: a history of forestry in francophone West Africa, IIED, London, 2001.

Sawadogo, L.: Etat de la biodiversité et la de production des ligneux du Chantier d'Aménagement Forestier du NAZINON après une vingtaine d'années de pratiques d'aménagement, Ouagadougou, CIFO, 2007.

Tanyi, T. F.: Sustainability of community forest in Burkina Faso: Case of CAF Cassou, Master, Department of Forest Science, University of Helsinki, 2017.

Wardell, D. A. and Lund, C.: Governing access to forests in Northern Ghana: Micro-politics and rents of non-enforcement, World Dev., 34, 1887–1906, 2006.

Zougouri, S.: Derrière la vitrine du développement: Aménagement forestier et pouvoir local au Burkina Fas, PhD, Uppsala Universitet, 2008.

There is no existing national map of the different CAFs of Burkina Faso, although the government is currently delineating the CAF areas. One reason why such a long-standing program as the CAF has produced no overall cartographic representation of its achievements is that the boundaries of CAF areas are actually more dynamic than its technical specifications, such as the rotational plots described here, would suggest. For example, within one of the original CAF areas, residents are currently negotiating that part of the areas be declassified based on the existence of their own agricultural fields in this areas (Forest Services, personal communication, 2017). This kind of politics over boundaries and the absence of maps for CAF areas support our analysis of the CAFs as a “political forest” – as sites of struggle over state territorialisation. Further research on national cartographic representations of CAFs would be very valuable as they would shed further light on the technologies through which CAFs are reproduced as “political forests”.

There are also ongoing discussions at the national level for the institutionalisation of a communal tax on fuelwood production – see Côte (2015) and Karambiri (2015) – but this has not been officially instituted yet.

See p. 2 and 7 of https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/sites/default/files/meeting-documents/burkina_faso_response_to_us_and_uk_comments.pdf (last access: 13 January 2018). The Climate Investment Fund is a World Bank funded project that is involved in Burkina Faso through the Forest Investment Program that aims to introduce carbon market schemes through forest management initiatives; see MEDD, 2011).

Tiis naaba is also the vernacular term to qualify the official forest agent in Mooré, but here we use it to refer to unofficial local authorities over the bush.

This is the equivalent of EUR 1.10.

A government document reported that there are currently around 1000 ground-level forest agents hired, which amounts to 1 agent for 25 000 to 100 000 ha areas (Dié, 2011:52).

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Of “political forests” and “fuelwood territorialities”

- CAF as the “political forest” of Burkina Faso

- Merchant fuelwood territoriality inside CAFs

- Customary fuelwood territoriality outside CAFs

- Conclusion: seeing the fuelwood territorialities from the trees

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Of “political forests” and “fuelwood territorialities”

- CAF as the “political forest” of Burkina Faso

- Merchant fuelwood territoriality inside CAFs

- Customary fuelwood territoriality outside CAFs

- Conclusion: seeing the fuelwood territorialities from the trees

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- References